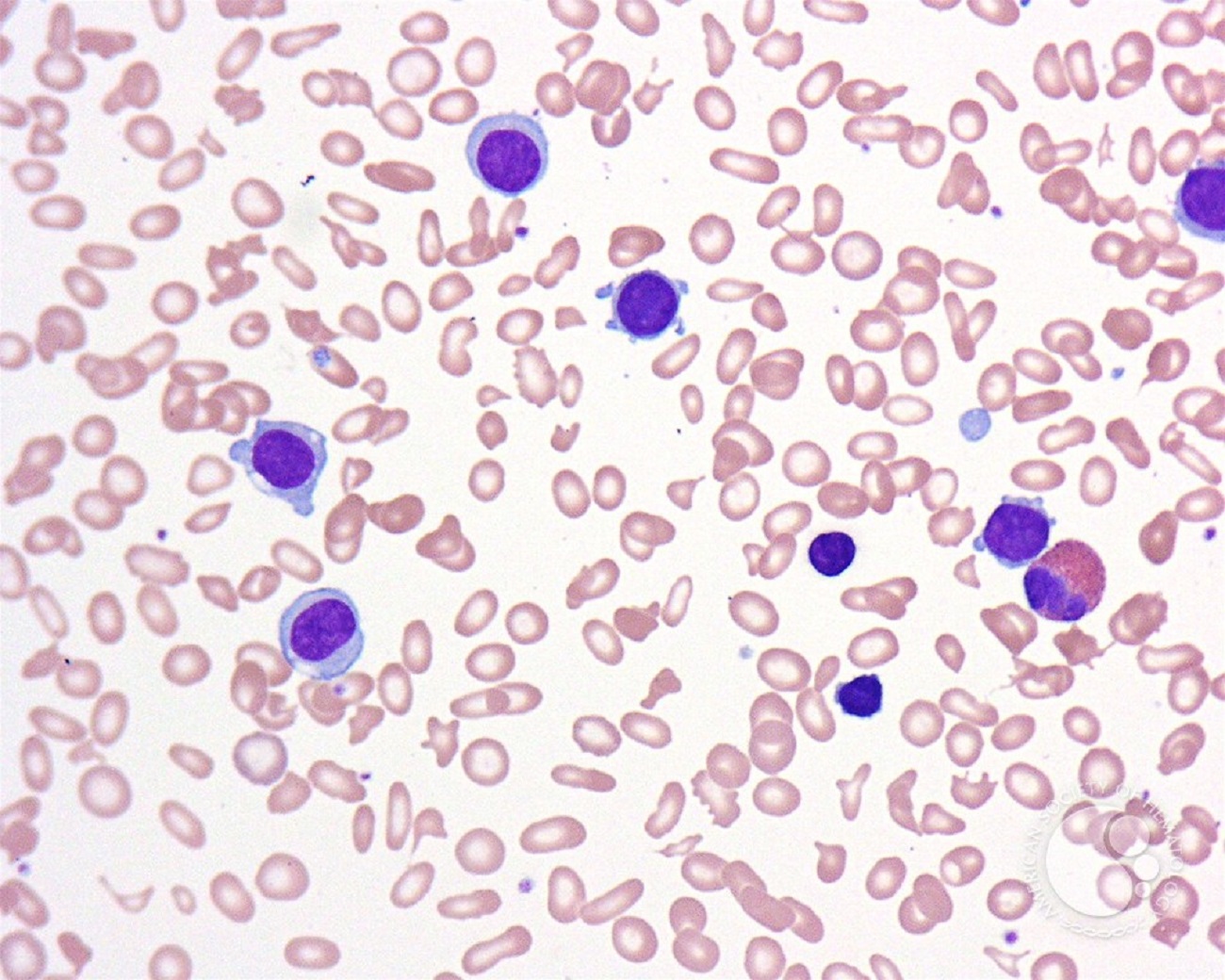

Hairy cell leukemia (HCL) is a rare, slow-growing disease that responds to initial treatment. Chemotherapy with purine nucleoside analogs either given alone or with rituximab are the mainstay therapy for newly diagnosed symptomatic patients leading to five-year survival rates in excess of 90% of patients. Despite this progress, our important work continues because there is still no cure for HCL, some patients do not respond to treatment at all, and many patients relapse at some point after treatment. Therefore, LLS is committed to funding research to help find better treatments for initial disease as well as relapsed cases.. Fortunately, with the discovery new drug technologies as well as molecular defects specifically found in HCL patients, alternative therapies have been identified.

Are you a Patient or Caregiver? Click here for our free fact sheet on HCL.

A major advance in the treatment of HCL was enabled by a technology that allowed wide scope, relatively rapid, mutational analysis of tumors. The so-called massive parallel sequencing method enabled Enrico Tiacci, M.D., at the University of Perugia in Italy (and subsequently other laboratories) to demonstrate that virtually all patients with a common form of HCL (known as classical HCL) have a mutation in a protein known as BRAF. BRAF is a known protein that induces cancer. Since vemurafenib is an inhibitor of BRAF and is an approved therapy to treat melanoma patients with mutant BRAF, LLS funded Dr. Tiacci to explore the use of vemurafenib in HCL. He and others were able to show that vemurafenib partially controls HCL. Moreover, LLS has funded additional work to show that other mutations immediately “downstream” in the BRAF pathway are found the so-called variant form of HCL. This work has enabled new therapeutic options for HCL patients.

As the work with vemurafenib was progressing, other LLS research investments were paying off for HCL. In 2008, LLS funded Curt Civin M.D. at the University of Maryland, who showed that an antibody directed to the surface of leukemic cells, which was attached to a toxin, was very effective at killing another leukemia, known as acute lymphoblastic leukemia. This finding ultimately paved the way for FDA approval in 2018 for what is now called moxetumomab pasudotox (Lumoxiti®) to treated patients with relapsed or refractory HCL (HCL-V). This FDA approval marked the first for HCL in more than 20 years and importantly, represents a promising non-chemotherapeutic agent for the disease.

LLS continues to invest in new research and therapies to further improve outcomes for HCL patients including:

- Enrico Tiacci, M.D. (University of Perugia, Italy) and team are now exploring if vemurafenib combined with an inhibitor of the pathway downstream of BRAF, or combined with a CD20-directed antibody that has superior properties compared to rituximab, designated obinutuzumab, controls tumor growth in relapsed HCL patients. The goal is to achieve long-term complete remissions.

- Jae Park, M.D. (Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center), is studying vemurafenib in combination with obinutuzumab, in previously untreated patients with classical HCL, and testing an ERK inhibitor (also downstream of BRAF) in patients with HCL variant and relapsed classical disease. In addition, the team is conducting genomic profiling of patient samples to understand treatment responses and disease biology.

More promising advancements for HCL are on the horizon, with an eye toward cytotoxic-free treatment regimens. Over the next few years, we can expect to see newer targeted inhibitors of BRAF and MEK inhibitors, along with monoclonal antibody therapy and next-generation immunotoxins. From optimizing combinations of therapies to harnessing the latest genomic technologies, our vision is to find cures and improve outcomes for patients with HCL.

As LLS looks into the distant future, there are particular gaps in our knowledge about HCL that should be addressed. They include:

- Epigenetic alterations. Little is known about the epigenetic changes that control the expression of certain proteins that drive HCL or lead to evasion of the immune system. Some of these genes are more frequently mutated in a HCL-V, which is a more aggressive disease than classical HCL. As more epigenetic inhibitors are identified and explored in clinical trials for other blood cancer, these new agents may have utility in HCL.

- Patient Registries. The longitudinal analysis of the progress of HCL suffers from a large retrospective analysis of an annotated data set (that has electronic health care records and biopsy information), let alone a prospective database of patients that will be treated with B-RAF and MEK inhibitors. As patient can survive for decades, large databases with samples collected over long duration, are needed to effectively conduct this analysis. This analysis may identify patients who are at risk of early relapse and therefore, require more aggressive therapy.

- Novel immunotherapies. HCL tumor cells have cell surface markers such as CD123, CD22, CD38, and CD25 which may be amenable to novel immunotherapies (i.e. CAR –T, bispecific antibodies, monoclonal antibodies, or antibody drug conjugates) that will specifically target HCL tumor cells with minimal, or surmountable side effects. CAR-T therapy, using a single dose, has proven highly effective for certain leukemias and lymphomas. Such immunotherapies may be useful in HCL. An antibody to CD38, daratumumab, has already proven safe and effective in myeloma. Daratumumab may be useful in HCL.

The image was originally published in ASH Image Bank. John Lazarchick. Hairy Cell Leukemia Variant 1. ASH Image Bank. 2007;3321. © the American Society of Hematology.