David Traver, Ph.D., a professor of Cellular and Molecular Medicine at the University of California, San Diego, is the recipient of an LLS Career Development Program (CDP) grant. Traver’s research laboratory is using the zebrafish as a model to study the biology of cancer.

David Traver, Ph.D., a professor of Cellular and Molecular Medicine at the University of California, San Diego, is the recipient of an LLS Career Development Program (CDP) grant. Traver’s research laboratory is using the zebrafish as a model to study the biology of cancer.

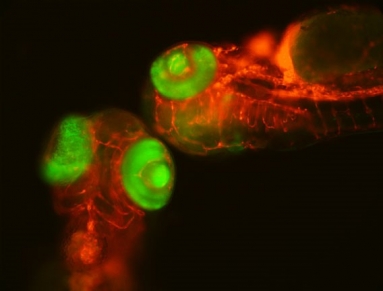

Most of his team’s studies are aimed at understanding how the hematolymphoid system arises in the zebrafish embryo from the first hematopoietic stem cells. The zebrafish system offers easy visualization of blood cells in the translucent embryo and the ability to dissect pathways genetically.

In the simplest of terms, how would you summarize what you are hoping to do?

Our main question is how hematopoietic stem cells (HSCs) are born in the vertebrate embryo. There are several waves of blood cell formation during the development of all vertebrate animals, but only HSCs are conferred with the ability to self-renew for life. We are working to understand the genetic basis of how this self-renewal program is formed, since self-renewal is the key to stem cell function over time and also what is inappropriately conferred to cancer-initiating cells. If we can understand how normal self-renewal programs operate, we believe we can understand how these programs are co-opted by the leukemogenic process to give rise to leukemias.

What is the biggest challenge your team faces?

Our biggest challenge is to keep our research programs funded. The funding climate in the U.S. is still incredibly challenging, especially for ideas that are unconventional or ambitious. The 5-year award from LLS has been a great help in providing stability to my group.

Why did you decide to use zebrafish to study blood cell development?

Following my Ph.D. studies on hematopoietic stem and progenitor cells in the mouse, I turned to the zebrafish system as I wanted to learn more about genetics, developmental biology, and in vivo imaging -- all noted strengths of the zebrafish. With the major blood cell types and signaling modules exceptionally well-conserved over evolution across vertebrate phyla, findings in one system almost always inform those in others. When I started working in the zebrafish system 15 years ago, there was very limited information and infrastructure in place for the study of stem cells in the zebrafish due to it being a relatively new animal model. Since then, the field has grown exponentially, and we now have an incredibly robust toolbox to complement studies of hematopoiesis in mouse and man.

Many non-scientists don't fully appreciate the value of basic research. How would you convince a cancer patient of the importance of your research, and how it may impact blood cancer diagnosis or treatment in the future?

For many blood cancers, there remain few effective treatments. Modeling these cancers in new ways may thus be the key to a better understanding of how to beat them in patients.

Do you have plans to use the zebrafish to model blood cancer? If so, how might those studies complement research done using patient samples?

Yes. We have been working to model pediatric leukemias in the zebrafish, most notably those involving translocation of the human MLL gene. There is very little hope for children that develop this particular type of disease, so we hope that new models will yield new insights into the biology of this leukemia. Once we develop robust models of MLL+ leukemia, we will work to identify new small molecule drugs that are effective against this disease.

Read Q&A's with other LLS-funded researchers here.