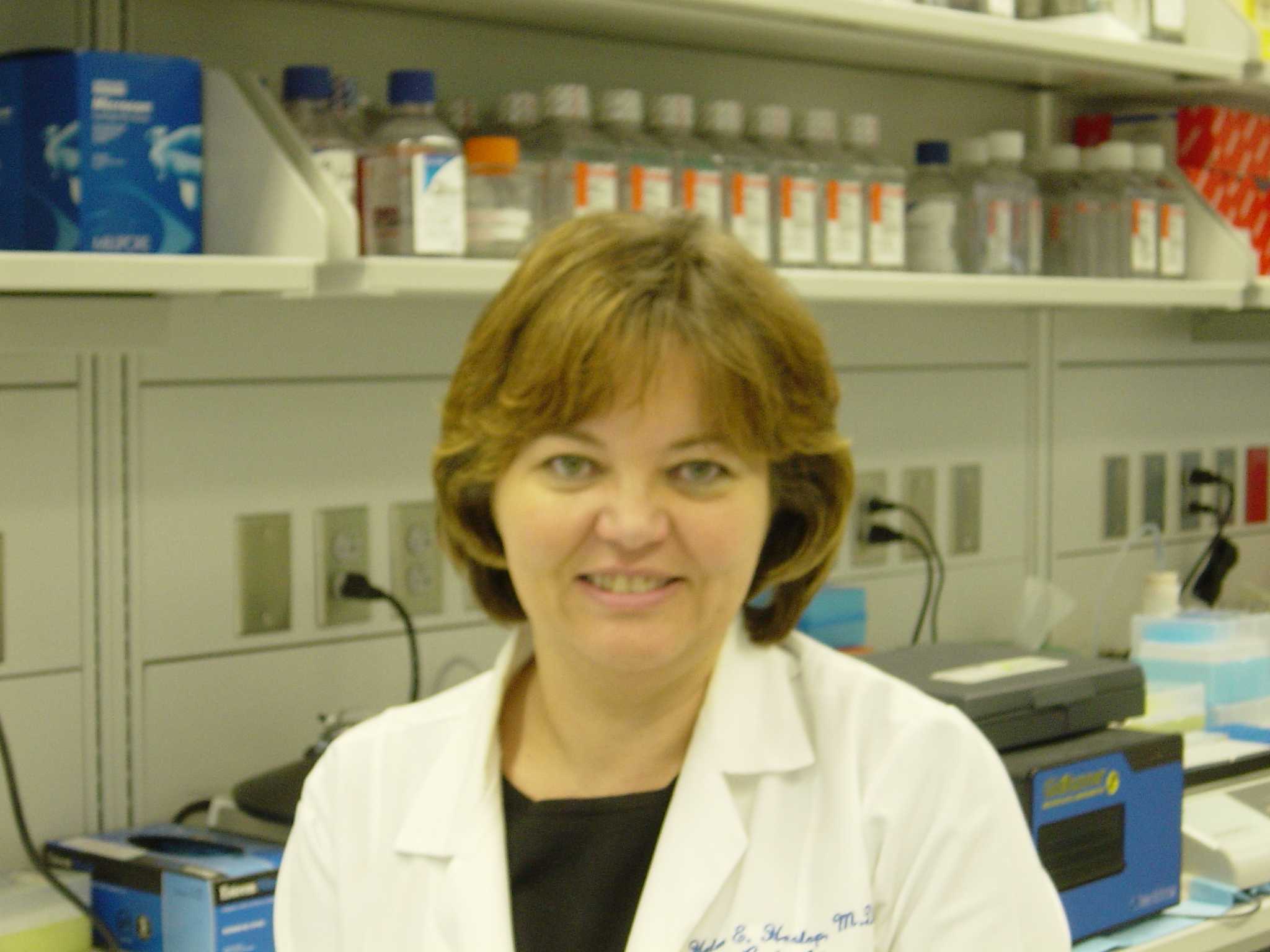

Helen Heslop, M.D., leads a team of scientists being funded through LLS’s Specialized Center of Research Program (SCOR). The project brings together researchers from different institutions to test a half dozen novel approaches to cancer immunotherapy – all of which harness the patient's own immune system to fight the cancer. Heslop, a professor in the Department of Medicine and Pediatrics at Baylor College of Medicine and the director of the Center for Cell and Gene Therapy, pioneered the adoption of T-cell immunotherapy for lymphoma and now proposes to translate this early success to additional blood malignancies, including multiple myeloma and acute leukemia.

In the simplest of terms, how would you summarize what you are hoping to do?

Our team is trying to develop immunotherapy approaches that we hope will kill tumor cells while sparing normal tissues and avoiding the toxicities associated with intensive chemotherapy. We want to address several pivotal issues whose resolution will make T cell immunotherapy more effective, simpler, safer and accessible to a broader cross-section of patients with leukemia, lymphoma or myeloma.

Dr Leen, a SCOR investigator, removes frozen patient cells from a liquid nitrogen freezer

Immunotherapy is getting a lot of attention these days. Why is it such a game changer?

Immunotherapy has the potential to provide a very specific treatment to eliminate the cancer and then, because of the way the immune system boosts the body’s own defenses, have a long-term effect.

Are we talking about cures?

We hope so but many of the new approaches such as CD19 CAR-modified T cells for acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL) do not have enough follow up yet to know how many patients will have long-term remissions. In the bone marrow transplant setting though – which of course was the original immunotherapy – many patients are long-term survivors. We also have patients with Epstein-Barr virus (EPV)-dependent lymphoma who were treated with EBV-specific T cells nearly 20 years ago and remain in remission.

Your laboratory has already proven that antigen-specific cytotoxic T-cells can kill cancer cells in some lymphoma patients. What approaches are you studying now?

We have a diverse team studying several approaches. Drs Rooney, Rouce and I are doing a trial to ask whether banked, or “off-the-shelf” T-cell preparations can be used successfully to treat virus-related lymphomas. Drs Leen, Lulla, and Brenner are undertaking a clinical trial of T cells that have been stimulated to recognize five proteins in patients with myeloma while Dr. Metelitsa has developed a novel vaccine taken by mouth that can cause the body to make an immune response against one of these proteins. Drs Dotti and Savoldo are testing an artificial receptor, called a CAR, that recognizes a protein called CD138 expressed by myeloma cells. Dr. Bollard is running a clinical trial to give T cells that recognize four proteins on leukemia cells to patients who have received a stem cell transplant for ALL. Finally, Dr Gottschalk is testing a novel new molecule called a CD19 engager, which will be released by the T cells to bind to and kill leukemia cells by recognizing a structure on their surface called CD19.

T-cell-based immunotherapy has been a promising research topic for some time now. Why is it so difficult to translate these learnings into therapies that will extend and improve the lives of blood cancer patients?

The manufacturing has historically been complex and so it has been a “boutique” application only available in a few centers. But a number of advances with new compounds and manufacturing techniques for growing cells have meant that the strategies can now be tested in later phase trials. Indeed several companies are now undertaking multicenter trials of T cell therapies and I expect some will be approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration in the next year or so.

How do you see blood cancer patients being treated differently 10 years from now?

I hope the therapies will be much less toxic for the patient than they are now and will include combinations of immunotherapy agents -- for example, tumor-specific T cells and a checkpoint inhibitor – with other targeted agents. More rapidly available genetic analysis of tumors will predict tumor-specific targets for immunotherapy.

Read Q&A's with other LLS-funded researchers here.