If you want to get technical, I have cancer. At least I think I do. I was diagnosed eight years ago with chronic myeloid leukemia (CML) and while there are no longer any signs of disease in my bone marrow, this is a condition that never really goes away. The cancer-causing enzymes keep firing and my daily Gleevec pills continue pummeling them into submission.

If you want to get technical, I have cancer. At least I think I do. I was diagnosed eight years ago with chronic myeloid leukemia (CML) and while there are no longer any signs of disease in my bone marrow, this is a condition that never really goes away. The cancer-causing enzymes keep firing and my daily Gleevec pills continue pummeling them into submission.

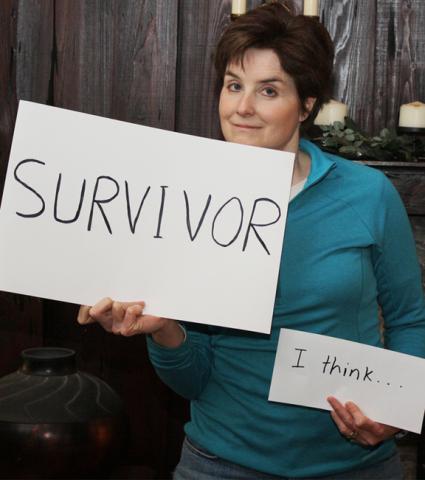

I like to think of myself as a cancer survivor, but dare I be so cocky? Not only do I not want to tempt fate, but it feels a bit like I’m staking claim to a territory I’m not fully entitled to. After all, I didn’t go through bouts of chemotherapy and extensive hospital visits, lose my hair, and give up months (or years) of my life. All I did was start taking a pill once a day and master the art of living in a suspended state of disbelief.

Since my diagnosis in 2006, I’ve slowly moved out of the “Oh my God!” phase and settled into a mindset more along the lines of Doris Day’s: “Que Sera Sera.” The world does look a little scarier from where I stand but I try to accept the fact that there’s not a whole lot I can do about it. I tell myself every day that things could be a whole lot worse.

Being normal

Initially, when I told people I had leukemia, they would burst into tears or look shell-shocked. Eight years later, most have forgotten and I can’t always remember who I’ve told. At this point, I just want to be a “normal” person and not let my diagnosis define me. Still, anyone who’s had cancer knows that once people hear that word, they never look at you quite the same way.

My first husband feared the label so much that he didn’t want anyone but family and close friends to know he had advanced prostate cancer. When a neighbor noticed him limping in the yard I said he probably pulled a muscle. His co-workers may have noticed his increasing absences and exhaustion but it wasn’t until weeks before he died that they learned why.

My cancer is going to be with me a long time so I don’t mind talking about it. I also know there is a level of stress involved in living with a secret, especially one that has the potential to kill you. But should I bring it up? Would I want to, and how exactly do I fit it into a conversation? Should I mention it with new friends or when starting a new job? It’s not something I want to wear on my sleeve but I don’t want to hide it either. I’m proud of the fact that I’ve made it this far and to be honest, I wouldn’t turn down a pat on the back every once in awhile. Nobody can offer support if they don’t know.

On one hand, I feel a little upbeat that I’ve been nudged into setting my priorities. A life-threatening diagnosis works a bit like a magnifying glass, making everything look a bit more precious and allowing you to zero in on the finer details. I’m thankful every day for the opportunity to marry again, get a new job I’m passionate about (with The Leukemia & Lymphoma Society!), spend time with friends and family, volunteer for a pet rescue group, and keep up on the news about a world I don’t plan to leave any time soon.

On the other hand, I do live with a perpetual cloud over my head, continually wondering when it might start to pour. What if someday those magic pills stop working?

What are my chances?

With CML, there isn’t really a remission, at least not the way most people know it. It’s all about response. CML patients aim for a “complete molecular response” -- undetectable levels of the cancer-causing BCR-ABL protein in the bone marrow. Once you make it to that point, the chances of the disease progressing decrease drastically. Yet most people with CML never get there. Taking Gleevec -- or another tyrosine kinase inhibitor (TKI) -- is intended to keep the disease from moving into an accelerated or blast phase, but there’s no way to know whether every cell is free of that nasty Philadelphia chromosome.

Fortunately, a new spate of drugs have turned a previously fatal cancer into a chronic condition where those newly diagnosed have a 95 percent chance of living a normal life. Knowing you have to take a medication for life isn’t fun but it would be considerably less fun to be dead. I was surprised to find a 2009 study in Blood magazine that noted that only 14 percent of people take Gleevec as prescribed. A full 71 percent take less – meaning they miss doses. Are they crazy? These have to be the same people who chain smoke and drive without a seatbelt. How can compliance be so poor when the potential consequences are so great?

The relapse rate is extremely low for people who have responded well to Gleevec for years. Patients from the landmark IRIS trial (International Randomized Study of Interferon Versus STI571), who have now been followed for eight years, continue to give the rest of us great hope. They have shown long-standing hematologic and cytogenetic responses, low progression rates to accelerated phase or blast crisis, and remarkable survival outcomes. A full 93% of those consistently taking Gleevec lived for at least eight years -- and they’re still going strong!

All of this should give me encouragement (and it does) but I have to confess that by nature I’m a nervous Nelly. What’s up with that other 7 percent? And what about all the people in the study who couldn’t tolerate Gleevec and switched to one of the second-line drugs such as Tasigna and Sprycel? Some people have great success that way and only a small percentage of individuals stop responding to one drug or the other, but I also know that the majority of those cases have grim outcomes.

I do feel very hopeful for those who were diagnosed more recently and were able to start on one of the second-generation TKIs, as they have been shown to achieve a superior molecular response or a higher rate of complete molecular/cytogenetic response than Gleevec.

Living in this gray zone isn’t easy. I would much prefer definitive answers. Why can’t everyone have a good outcome? I know many researchers are focusing their careers on that question and my fingers are crossed. For now, however, I’m making it my job to just keep taking my pills and keep my eye on those priorities.

This blog is the third in a series. Read:

Blog #1: "The Diagnosis"

Blog #2: "The Pill"

LLS offers many resources on CML: contact an information specialist, participate in a CML discussion board or online chat, get a free booklet on CML, and watch a video about the role of PCR (polymerase chain reaction).