More than 20,000 cancer scientists from around the globe came to Chicago this week to share and learn about the latest advances in research and treatments at the annual meeting of the American Association of Cancer Research (AACR). AACR is one of the world’s oldest and largest nonprofits dedicated to cancer research and education.

Blood cancers were among the thousands of scientific presentations and educational sessions. And while much of the excitement focused on lung cancer and other solid tumor cancers (as opposed to those of the blood), it should be noted that most of the concepts and approaches being discussed originated in blood cancer research – and this is promising news for the cancer community at large.

Immunotherapy Continues to Prove its Mettle

Several presentations unequivocally showed that an immunotherapeutic approach called checkpoint inhibitors is transforming lung cancer treatment. Checkpoint inhibitors work by launching an immune system attack on cancer cells.

In one practice-changing study in particular, a therapy called pembrolizumab (Keytruda®) in combination with chemotherapy resulted in a remarkable 50 percent reduction in patient deaths in a clinical trial for patients with non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC), the most common form of the disease.

Even though adding pembrolizumab to the chemotherapy regimen has been approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) since May 2017 as a first-line treatment for NSCLC, the current standard of care for these patients remains chemotherapy alone, sometimes accompanied with surgery. The results presented on Monday left no question that this checkpoint inhibitor/chemo combination should now become the standard of care for these patients.

Checkpoint inhibitor drugs are approved for various advanced solid tumor cancers, including melanoma, metastatic non-small-cell lung cancer, squamous cell carcinoma, bladder cancer, kidney cancer, urinary tract cancer and others. The checkpoint inhibitors pembrolizumab and nivolumab (Opdivo®) are also both approved for Hodgkin lymphoma patients who have relapsed from standard therapy.

Blood Cancer Research Opened the Door

A foundational component of the checkpoint inhibitor is the monoclonal antibody – a therapy that was first approved for use in blood cancer in 1997. This is rituximab, which is used to treat non-Hodgkin lymphoma, and later for chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL) and autoimmune diseases such as rheumatoid arthritis.

The body’s immune system produces antibodies to fight infections and the monoclonal antibody is a protein designed to attach itself to one specific type of protein, called an antigen, found on the surface of cells, including cancer cells. Rituximab was the first such monoclonal antibody approved by the FDA. This was quickly followed by the approval of Herceptin in 1998 by the FDA. Since then, more than a dozen others have followed for multiple types of cancer, each designed to target a specific antigen. These antigens are often overexpressed on the surface of cancer cells, making them attractive targets for monoclonal antibody therapy.

The checkpoint inhibitors, pembrolizumab and nivolumab, employ a monoclonal antibody designed to target an antigen called the programmed death protein 1, or PD1. PD1 regulates the immune system by suppressing T cell activity. Cancer cells hide from the immune system by inducing the PD1 protein to put the brakes on the T cells, the workhorses of the body’s immune system. By targeting the PD1 protein with the antibody, the immune system is unleashed to kill the cancer cells.

Studies presented at AACR for anti-PD1 antibodies for melanoma and other diseases also showed promising results.

CAR T-Cell Immunotherapy Makes Steady Gains, but Can it Work in Solid Tumors?

Another immunotherapy method that began with blood cancers is chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) T-cell immunotherapy, an approach that reprograms a patient’s own immune T cells to find and kill cancer cells. The therapy is revolutionizing treatment for two types of blood cancers, acute lymphoblastic leukemia and non-Hodgkin lymphoma, in patients whose cancer returned after multiple treatments or who did not respond to treatment at all.

But now the question is: Can it work in other types of cancers?

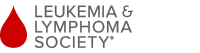

This question was the hot topic of a session on Monday at the AACR meeting. Carl June, MD, University of Pennsylvania, who pioneered CAR T-cell therapy with LLS support over the past two decades, showed a photo of one of his first leukemia patients to be treated with CAR T-cell therapy, a CLL patient still cancer-free seven years after treatment.

Dr. June said his lab is now attempting to develop the therapy in patients with solid tumors.

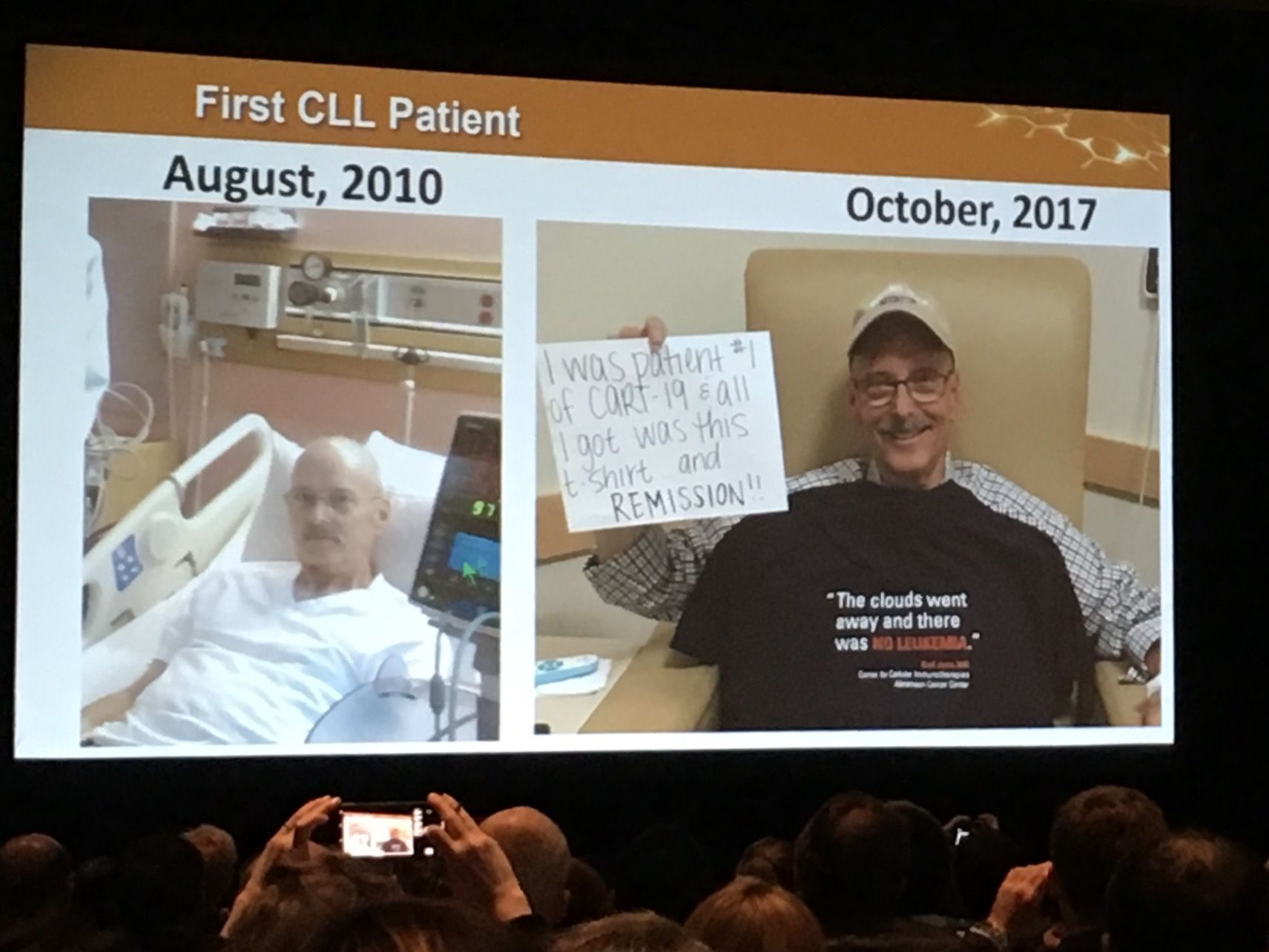

Dr. June and other scientists discussed their efforts to pursue CAR T-cell clinical trials in cancers such as glioblastoma, pancreatic and ovarian cancer. There are glimmers of hope, but many obstacles remain.Scientists need to figure out the right antigens to target in solid tumors, without the risk of attacking the organ’s healthy cells along with the cancerous ones. It’s also more difficult to get the CAR T-cells to reach the solid cancer tissue, compared to the ease of accessing cancerous cells in blood. In the blood cancers, the T cells continue to proliferate once they are returned to the patient’s body – becoming a virtual living drug. Scientists are trying to determine how to make the CAR T-cells endure in solid tumors.

Additionally, a concept gaining speed in CAR T-cell immunotherapy centers on creating so-called “off-the-shelf” versions that would use a donor’s cells rather than the patient’s own, which are highly personalized and time-consuming to produce. These off-the-shelf versions would be more easily mass-produced, thus, more accessible to more patients and, hypothetically, less costly. One of the main challenges is to overcome the dangerous risk of the patient’s own immune system attacking the donor cells, resulting in the potentially fatal graft versus host disease (GvHD). Bob Valamehr, Ph.D., of Fate Therapeutics Inc., presented on an off-the-shelf therapy called FT819. The therapy has not been tested in patients yet, but it seeks to minimize the risk of GVHD by deactivating the T-cell receptor, thought to be the cause of the deadly syndrome.

More Hope for Precision Medicine

Precision medicine is an innovative model of healthcare that centers on giving the right treatment to the right patient at the right time. An example of this therapeutic approach is a family of therapies called tyrosine kinase inhibitors (TKIs), which also have origins in blood cancer research. Kinases when they are overexpressed or mutated, often lead to proliferation of malignant cells. The first TKI to achieve FDA approval was imatinib (Gleevec®), approved for chronic myeloid leukemia in 2001, and subsequently for other types of cancers. LLS supported the work of Brian Druker, MD, of Oregon Health for this groundbreaking drug, opening the gates for a flood of kinase inhibitors for multiple types of cancers. At AACR, a novel kinase inhibitor that drew attention was BLU-667. BLU-667 takes a precision medicine approach to treating patients by targeting the genetic mutation, called RET, found in multiple types of tumors, including thyroid, NSCLC and others, rather than focusing on the site of the tumor. The therapy is in early-stage clinical trials.

Key Takeaway:

From monoclonal antibodies to the next generation of CAR T-cell immunotherapy, progress in blood cancer research is helping to advance important breakthroughs in solid tumor cancers and other diseases.