UPDATE: The U.S. Food and Drug Administration on August 5, 2020, approved belantamab mafodotin-blmf (Blenrep®; GlaxoSmithKline/GSK as a monotherapy treatment for adult patients with relapsed or refractory multiple myeloma, who have received at least four prior therapies including an anti-CD38 monoclonal antibody, a proteasome inhibitor, and an immunomodulatory agent.

News in mid-July that a special committee of the U.S. Food & Drug Administration called ODAC (Oncologic Drugs Advisory Committee) had ruled favorability on an investigational treatment for relapsed myeloma came as somewhat of a surprise. After all, some reviewers within the FDA have expressed serious concerns about toxicity of the drug affecting patients’ eyes, including blurred vision or dry eye, and even severe corneal ulcers that may require corneal transplant.

But on Tuesday July 14, the 12-member ODAC committee determined the benefits outweigh the risks, and voted unanimously to recommend the drug, belantamab mafodotin, be approved by the FDA. That FDA decision is due in August. The ODAC decision is based on a Phase 2 clinical trial that divided the patients into two cohorts, each receiving a different dose of the drug. The overall response rate (ORR) observed in the 97 patients who received the lower dose of belantamab mafodotin was 31%. For the 99 patients who received the higher dose of belantamab mafodotin, the ORR was 34%.

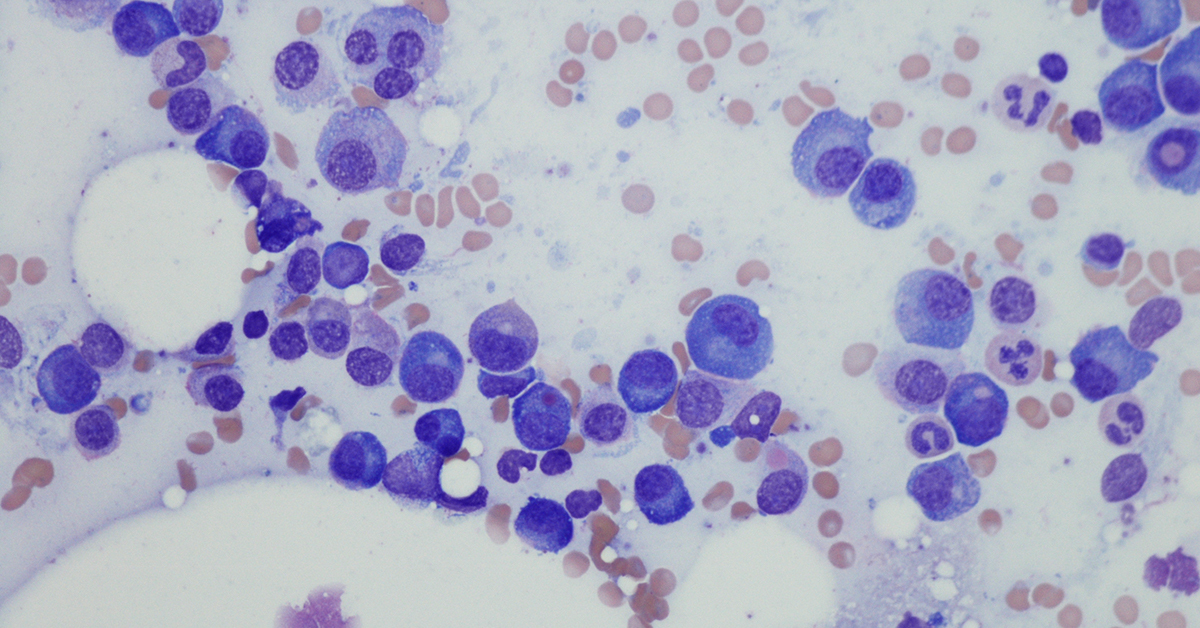

The reason this decision is so significant is that, if approved, belantamab mafodotin would be the first of an emerging approach to treating myeloma that has sparked intense interest and scrutiny. Belantamab mafodotin is among a growing number of experimental therapies designed to target a protein on the surface of myeloma cells called B-cell maturation antigen (BCMA). This cell surface receptor is present on virtually all multiple myeloma cells but is absent from normal B cells, making it an ideal target for therapy.

Belantamab mafodotin is an antibody-drug conjugate, meaning it is comprised of an antibody bound to a toxic molecule. The antibody homes in on the BCMA on the cell surface and the cancer-killing molecule is released into the cell and causes cell death.

Progress Treating Myeloma

For decades, multiple myeloma was one of the most challenging blood cancers to treat, with combinations of chemotherapy and steroids offering a life expectancy of about three years at the most. Approximately 32,000 people are diagnosed each year with myeloma, and about 12,800 will die from it.

The disease remains incurable, but over the past 15 or so years, a dizzying array of new therapies, including targeted and immunotherapies, has changed the prognosis for many patients suffering from this disease that afflicts the blood plasma cells in the bone marrow.

These more recent advances have extended life and are bringing tremendous relief to patients, most of whom experience painfully brittle bones and many other excruciating and life-threatening symptoms.

Now these BCMA-targeting therapies are emerging as the next potential breakthrough for myeloma patients.

Right on the tail of belantamab mafodotin are a number of chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) T-cell therapies also targeting BCMA.

As I reported in this blog in June, multiple companies have presented compelling data on BCMA-targeting CAR-Ts.

CAR-T, a treatment approach LLS helped to pioneer and has supported for more than 20 years, turns the body’s own immune T cells into supercharged cancer-killers. With LLS support, the therapy has achieved approvals for children and young adults with acute lymphoblastic leukemia, and adults with non-Hodgkin lymphoma. LLS is supporting work in BCMA-targeting CAR-T, including a Specialized Center of Research grant led by Madhav V. Dhodapkar, MBBC, of Emory University, who is studying why some patients become resistant to BCMA-targeting CAR-T.

These BCMA-targeting therapies have the potential to bring real hope for myeloma patients who have relapsed at least three times from prior treatment. And if further study proves these therapies can bring durable remissions, they could potentially be used even earlier in the treatment of patients who still desperately need better options.